> Haweswater Aqueduct 📍

The 56 mile underground Haweswater Aqueduct is another feat of engineering drawing water from the Lake District to supply Manchester. It was started in 1935, 10 years after the Thirlmere Aqueduct was completed in 1955 (although later improvements were made in the 1970s).

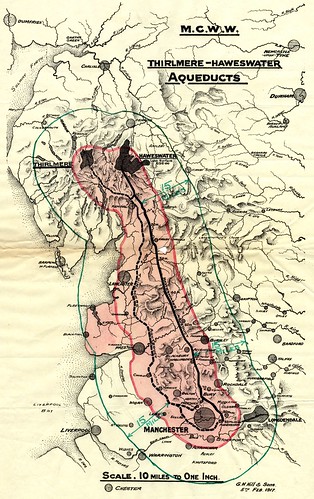

[after the 96 mile Thirlmere Aqueduct was completed…] Subsequent schemes in the Lake District saw Haweswater dammed, raising its water levels significantly, and the construction of a separate aqueduct south to the city. Subsequently, connections to other sources in Cumbria have augmented this supply.

The construction of the aqueduct followed the creation of Haweswater Reservoir, by a controversial scheme to dam the valley of Mardale. The scheme involved flooding the picturesque villages of Measand and Mardale Green. Hundreds of people were forced to leave their homes which were then blown up by the Royal Engineers for demolition practice. The church was spared from demolition by explosives, and was dismantled and the materials used to build the water take off tower. In addition 97 bodies were transferred from the graveyard. In dry times when waters are low remains of the villages can be seen above the water level, often prompting news stories.

Before the valley was flooded in 1935, all the farms and dwellings of the villages of Mardale Green and Measand were demolished, as well as the centuries-old Dun Bull Inn at Mardale Green. The village church was dismantled and the stone used in constructing the dam; all the bodies in the churchyard were exhumed and re-buried at Shap. Today, when the water in the reservoir is low, the remains of the submerged village of Mardale Green can still be seen as stone walls and the village bridge become visible as the water level drops.

You can read more about the aqueduct’s history on Tatham History. There is also a great article on the Manchester Evening News titled “How Victorian water engineers put Manchester on the tap” which gives a good summary of the engineering behind Manchester’s water. The aqueduct carries 570 million litres a day—more than double what the Thirlmere Aqueduct carries. Although almost entirely underground, the aqueduct’s route can often be observed by above ground marks, and numerous inspection hatches. There are also a number of buildings, although these are not quite as regular and valves to release trapped air. With six tunnels of 2.6 metre diameter, 31 miles of the aqueduct are big enough to walk / drive down. The remaining 32 miles are made up of four buried pipes between 1.2 metre and 1.4 metre diameter. The weight of the water over the 550 metre drop from Haweswater Reservoir sucks the water over a number of uphill sections—the whole system essentially acts as a massive siphon.

Metal pedestrian access gates through field boundaries mark the line of the pipeline, provided for inspectors who supposedly regularly walked the pipeline before the days of helicopters.

Our #Haweswater aqueduct clean is going well. Here's our aquanauts arriving after a long journey under Bowland Forest pic.twitter.com/5h2woTjUcl

— United Utilities (@unitedutilities) October 15, 2013

Cleaning the Haweswater aqueduct

In October 2013 United Utilities sent 80 specialist engineers dubbed aquanauts into the aqueduct using special buggies to survey, clean and repair it (BBC: Kendal aquanauts set for Haweswater Aqueduct mission) over a two week period with no impact to the public… quite a task! They were so proud they produced a commemorative brochure.

The Haweswater aqueduct is 90km long, hundreds of feet deep in places, and allows 570 million litres of water to flow from Cumbria to Manchester every day. It took over 20 years to build and was commissioned in 1955 by the Manchester Corporation. The ‘mega-pipe’ provides the water supply for 2 million people across Greater Manchester. We invested £22 million on a detailed structural analysis of the pipe for the first time in its history.

A mammoth task and a decade in the planning, it wasn’t as simple as turning off a tap. Draining and shutting down the system to allow maintenance crews inside involved over 400 workers operating on 45 separate projects to ensure the network of supporting treatment works could ‘take the strain’ while Haweswater was offline.

Aquanauts 2: The Return

In July 2015 United Utilities announced that they would be sending aquanauts back into the aqueduct around the end of September 2015. This was to be a bigger exercise, with about 450 people involved in the project.

John Butcher from United Utilities said:

When we headed into the aqueduct it was a delight to step into a moment of history and see and touch the tunnel during the inspection.

The aqueduct has stood the test of time however; it does need a little TLC. While we’re in there this time, our aquanauts will be scanning every inch of the tunnel and fixing what they can.It’s going to take a team of around 450 people to successfully deliver this project. A bespoke training camp has been set up to make sure everyone is ready to hit the ground running on go live date at the end of September this year.

Paul Anderton, senior project manager added,

By working together, we should be able to offer a seamless service, and our customers’ won’t even notice us working hundreds of feet beneath their homes investigating and repairing the pipe that serves water to their taps.

Heaton Park Water Inlet Building

Finally after being cleaned at the Watchgate treatment works the Haweswater Aqueduct travels the remaining 1.5 miles to finish its journey at Heaton Park Reservoir where it joins the Thirlmere Aqueduct to supply Manchester with clean water. You can see photos of the beautiful interior and exterior of the listed inlet building on the Mainstream Modern site. The building incorporates a large relief by Mitzi Cunliffe (a british scultor who also created the iconic design for the BAFTA award) and inside there is some sort of model and a wooden relief plan on the wall depicting the route. More is written about the building’s merits on the Historic England list entry.

This small building is actually something of a monument, a testament to the worth of the massive engineering endeavours of generations passed.

Route Credit

I started plotting the route of the two Lake District aqueducts by using Tatham History which also has an awesome interactive map, Haweswater Aqueduct Access Gates and Thirlmere Aqueduct Access Gates by the Nutters Mobile Surveillance Unit. I spent hours poring over Google Earth and eventually a 1913–1914 OS County Series map of Lancashire and Furness which has the exact route of the Thirlmere Aqueduct marked.

I was then thrilled to find a Thirlmere Aqueduct Google Earth KMZ file and a Haweswater Aqueduct Google Earth KMZ file on a forum by seggy224 with the exact routes (although I was frustrated not to have found them earlier). They have put a considerable amount of time into tracing from Google Earth observations, Google Streetview stills and a lot of hard work. In fact they’ve done an excellent job… much better than I could have managed, so I was keen to use their data. I managed to make contact to obtain permission to use the data and have transformed the route from KMZ to GeoJSON using Mapbox for the conversion and jq to cut down the result (which included features for each surface structure—way too busy when plotted on the map).

Hidden Manchester Map

Hidden Manchester Map